1. Critical thinking

The text below is divided into four sections.

- The first section deals with the concept of ‘critical thinking’. What exactly is critical thinking? What are the characteristics of the critical thinker?

- Section two focuses on the question how critical thinking can be mastered.

The answer to this question follows logically from the six key lessons as formulated by Van Gelder. One of the key lessons is the importance of visualizing reasoning by means of argument maps. - The third section responds to the question of what argument mapping actually is, and briefly deals with the history and use of argument mapping.

- Finally, the last section is about Rationale, a program for argument mapping.

1.1 What is critical thinking?

Knowledge, skills and attitude

A short definition of critical thinking is: ‘the art of being right’. This briefly-worded definition may not be immediately and easily understood and, therefore, needs some further explanation. What critical thinking actually is may best be explained by describing the characteristics of the critical thinker. For, he – and ‘he’ also refers to ‘she’ – is equipped with knowledge, skills and an attitude, typical of the critical thinker.

Since the critical thinker is capable of actively and skillfully applying general principles and procedures of thought, as described in Topic 3, his judgments will prove to be most sound and accurate. To put it simply: he knows the principles and procedures of critical thinking, and is capable of applying them.

A critical thinker does not state a contention without due consideration, that is to say, not without founding it on sound reasons based on reliable sources; he evaluates the underpinning of claims; he is not blind to possible objections against his contention, and is capable of refuting them. Equipped with this knowledge, he is able to form a sound judgment on what to believe and what action to take.

The critical thinker is skilled in analyzing other people’s claims. He is able to recognize arguments in a text and spot those that are deficient. He is able to indicate flaws in an argument, to reveal hidden premises, and to recognize fallacies.

The critical thinker is characterized by an open and inquiring attitude – also with regard to his own opinions – and takes nothing for granted; he is focused on the truth, and weighs up pros and cons, both in structuring his own argument and in judging other people’s arguments. He is curious, is aware of the fact that things are often not what they seem to be at first sight, and is receptive to new information, even if it proves to be contradictory to his own opinions. His opinions are tentative, and may be adjusted over and over again. He knows that he, just like anyone else, has blind spots and takes them into account.

In short: a critical thinker is someone who is both willing and able to sharpen his mind, and who is willing and able to form a sound judgment.

1.2 How to develop your Critical Thinking Skills?

Basic principles

In his article Teaching Critical Thinking: Some Lessons from Cognitive Science (2005) Tim van Gelder formulates six basic principles on which Critical Thinking with Rationale is founded. These principles are partly about critical thinking itself, partly about how critical thinking skills are acquired, and partly about how critical thinking can best be taught. Van Gelder’s article can be summarized as follows:

- Critical thinking is hard

Humans are not naturally critical. Indeed, like ballet, critical thinking is a highly contrived activity. Running is natural; nightclub dancing is less so; however, ballet is something people can only do well after many years of painful, dedicated training.

To argue in support of an opinion or to provide evidence to justify a statement, these basic skills of general reasoning are not innate abilities. Critical thinking is what cognitive scientists call a higher-order skill. That is to say, critical thinking is a complex activity built up out of other skills that are simpler and easier to acquire, like linguistic competence and text comprehension. A two-week module will not make you a critical thinker. Critical thinking is a lifelong journey.

- Practice makes perfect

Let us take tennis, for example, which is a higher-order skill. To be able to play tennis, you must be able to do things like run, hit a forehand, hit a backhand, and watch your opponent. But mastering each of these things separately is not enough. You must be able to combine them into the coherent, fluid assemblies that make up a whole point. Reading a book on critical thinking will not develop your critical thinking skills. Mastering a skill takes lots and lots of practice and, preferably, so-called ‘deliberate practice’, that is, specific, determined and concentrated practice.

- Practice for transfer is necessary

Within a course, critical thinking should be practiced separately. Subsequently, students have to learn to apply the acquired knowledge, skills and attitude to other fields of their studies. The entire curriculum should challenge students to do so.

- Knowledge of the theory is a must

Having knowledge of a framework of concepts enables students to spot and define poor reasoning, and improve their capacity for self-monitoring and correction. Furthermore, theory provides the foundation for teachers to give feedback. Having command of the lingo is like having x-ray vision into thinking. For example, if you know what affirming the consequent is, you can more easily spot examples of poor reasoning, because reasoning fitting that particular pattern will be more likely to jump out at you.

- People are prone to belief preservation

People have intrinsic tendencies to be conservative and stick with their beliefs and convictions. Therefore, it is important that teachers set an example by constantly adopting a critical, open and inquiring attitude, and to encourage their students to follow this example.

- Argument mapping improves critical thinking skills

A core part of critical thinking is handling arguments. Visualizing arguments – argument mapping – stimulates the development of critical thinking skills. And Rationale offers a useful tool for that.

For a summary of this article in a Rationale map click here.

1.3 Argument Mapping

What is argument mapping?

Both research and experience in the field of education show that critical thinking skills improve with argument mapping. Argument mapping is, roughly, making a picture of reasoning. More precisely, it is the graphic depiction of the structure of reasoning and argumentation.

Typically, argument maps are box-and-arrow diagrams, a bit like flowcharts. Like mind mapping, for example, argument mapping belongs to the family of ‘thought mapping’. Argument mapping is distinctive in that it focuses exclusively on reasoning or argument structure, and is specialized for that purpose.

History of argument mapping

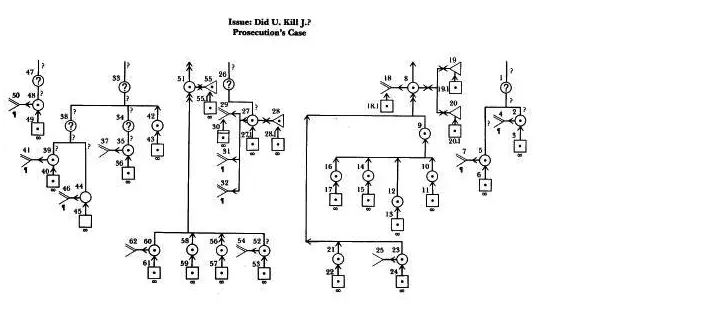

Argument mapping has a long history. It can be traced back to the work of Charles Wigmore, who in the early part of the last century produced maps of complex legal argumentation.

Figure 1.1

In 1958, philosopher Stephen Toulmin published his influential book The Uses of Argument, which presented a simple argument mapping scheme.

Figure 1.2

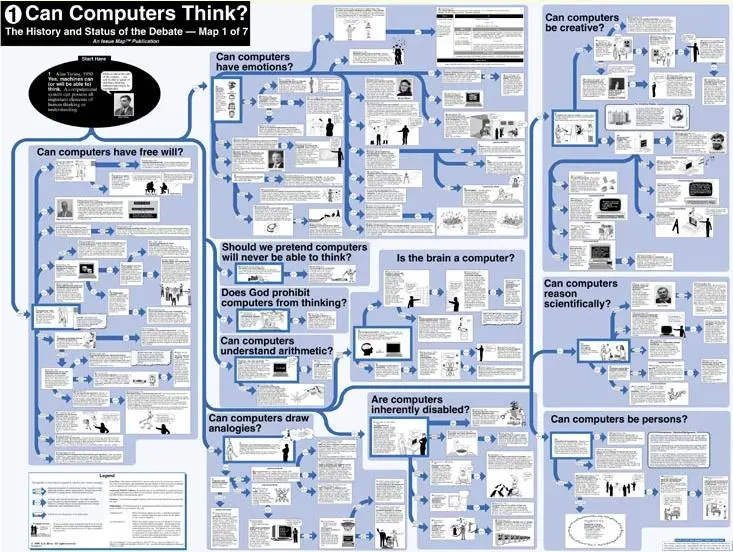

In the 1990s, with the arrival of the personal computer and graphics software, argument mapping started to become more widely used. One of the leaders in the field is Robert Horn, who has produced argument maps of very complex debates.

Figure 1.3

The most recent development has been the development of quality software tools / programs dedicated to producing argument maps, such as Rationale.

As you can see from these examples, there are many different kinds of argument mapping. What they have in common is the graphic rendition of evidential relationships, that is, how some claims are evidence for or against other claims.

Figure 1.4

Why Map Arguments?

There are many reasons to learn argument mapping:

- Argument mapping leads to better understanding. Graphical techniques enable your mind to deal more effectively with complex argumentations.

- Mastering the art of argument mapping will help build your general reasoning and critical thinking skills. Research conducted by Donahue et al. (2002), and Twardy (2004) and also Alvarez’ meta-analysis (2007) have shown that practice based on argument mapping is more effective than many other techniques for improving critical thinking.

- Argument mapping will help you produce a clear, strong, well-organized line of reasoning, which, after all, is a vital part of a convincing argument. Suppose, for example, you have to write an essay to defend your opinion. If you map out the relevant reasoning, you will become much clearer as to what it is, what you might need to add, its strengths and weaknesses and so forth.

- Argument maps will help you communicate your reasoning to other people. Ordinarily, we present reasoning in written or spoken forms, such as an essay or a debate. However, texts are very unreliable for this job. Very often, the reader or listener ends up forming quite a different interpretation of the reasoning than the one you intended. Argument maps are far more successful, because they present reasoning in a completely clear and unambiguous form.

- Argument mapping helps in the evaluation of reasoning, that is, deciding whether an argument is good or bad. Evaluation is crucial to critical thinking, since you should only accept things when they are backed up by solid reasoning. Argument mapping makes the structure of reasoning completely explicit, and so it helps you see strengths and weaknesses that would otherwise be obscured or hidden.

- Argument mapping helps people resolve disagreements rationally. Often in debates or arguments, people can have different interpretations of what the arguments actually are. Using argument mapping, people can share a common conception of the structure of the reasoning, and so agree or disagree about the substance of the issues, rather than being sidetracked by misunderstandings.

- Argument mapping can help you make better decisions. Anytime you need to make a decision on an issue on which there is a complex tangle of arguments, you will be better off when you map out the arguments to gain clarity and perspective.

- Finally, argument mapping can be interesting and fun! Of course, this is a matter of personal taste, but as a general rule the better you are at something, the more interesting and enjoyable you find it. We all engage in reasoning and argument every day, but most people do it quite badly. Somebody who has mastered argument mapping will be more likely to enjoy it.

The method Critical Thinking with Rationale includes a large amount of exercises with model answers enabling you to master argument mapping.

1.4 Rationale

Besides argument mapping, Rationale helps you write a well-structured and therefore more convincing argument.

In the following, Rationale shows you how to structure the necessary steps in the process of writing. After that, Rationale will show you, on the basis of an example, how to produce a well-written text.

Step 1. Organize Information

We have no difficulty in locating information. The key is that the information is selected and structured appropriately. With Rationale’s grouping maps you can drag information from the web onto your workspace and include color, hyperlinks and images. The structured, pyramid- like maps provide a guide for students to structure the information in such a way that reveals the connections between the main topic and its various themes or categories.

Figure 1.5

Step 2. Structure Reasoning

Many people provide opinions but rarely provide reasons to support their view. Rationale’s reasoning maps encourage people to support their responses, and to consider different opinions. It uses color conventions to display reasoning – green for reasons, red for objections and orange for rebuttals. It also includes indicator or connecting words, so that the relationship between statements is clearly understood.

Figure 1.6

Step 3. Consider Evidence

A test of a solid argument is how good the evidence is that underpins the claims. Rationale’s basis boxes provide a means of identifying the basis upon which a statement is given. The icons provide a visual guide as to the range of research utilized, and the strength of the evidence that is provided.

Figure 1.7

Step 4. Identify Assumptions

We often talk about analyzing arguments. This can mean a few things, including looking at the logical structure of the argument to ensure it is valid or well-formed, and also identifying assumptions or co-premises. For those who require higher levels of analysis, Rationale provides the analysis map format to show the relationships between main premises and co-premises.

Figure 1.8

Step 5. Evaluate Arguments

Once arguments for and against an issue have been logically structured, they need to be evaluated. Rationale provides a visual guide for the evaluation of claims and evidence – the stronger the color, the stronger the argument, while icons designate acceptable or rejected claims. While learning this process of evaluating arguments, color and icons provide immediate understanding and communication of the conclusion.

Figure 1.9

Step 6. Communicate Conclusion

Presenting ideas orally or in writing is crucial, and is often the distinguishing feature between good results and average ones. Rationale has essay and letter writing templates to build skills and confidence. Templates provide instruction and generation of prose. When exported, there is a structured essay plan with detailed instructions to assist an understanding of clear and systematic prose.

Figure 1.10

Example: ‘Wind farms…to be or not to be?’

Figure 1.11

Figure 1.12

Figure 1.13

Figure 1.14

Figure 1.15

Figure 1.16