Before you start...

This section covers some introductory material which should be useful before you start work on this tutorial:

- What is Argument Mapping? - a brief overview of argument mapping

- Why Map Arguments? - lists many reasons to map arguments

- About These Tutorials - gives general information about how the tutorial is designed and how you should use it

- Reading - Apollo Moon Landings - information about the article on which this tutorial is based. You should download and read this article.

- Producing Argument Maps - information about how to go about creating an argument map.

What is Argument Mapping?

Argument mapping is, roughly, making a picture of reasoning. More precisely, it is the graphical display of the structure of reasoning and argumentation.

Typically, argument maps are box-and-arrow diagrams, a bit like flowcharts. Argument mapping belongs to a family of "thought mapping" techniques which includes concept mapping and mind mapping. Argument mapping is distinctive in focusing exclusively on reasoning or argument structure, and is specialized for that purpose.

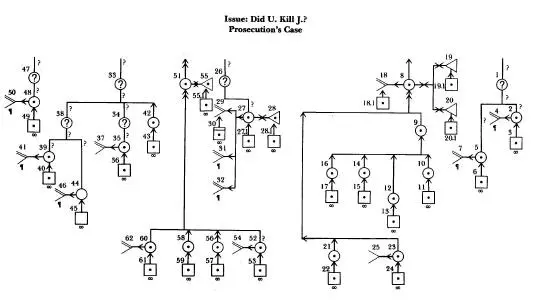

Argument mapping can traced back to the work of Charles Wigmore, who in the early part of last century produced maps of complex legal argumentation.

A Wigmore argument map.

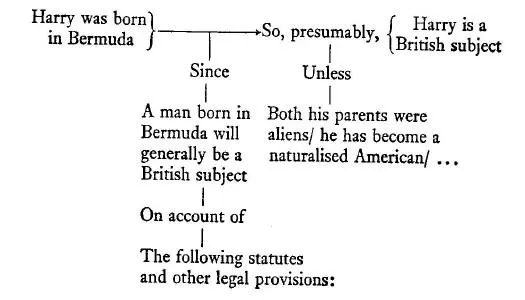

In 1958, philosopher Stephen Toulmin published The Uses of Argument, which presented a simple argument mapping schema. This work has had quite an influence.

A Toulmin argument map.

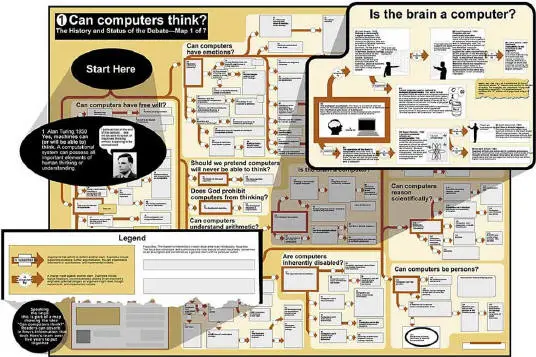

In the 1990's, with the arrival of personal computers and graphical software, argument mapping has started to become more widely used. One of the leaders in the field is Robert Horn, who has produced argument maps of very complex debates.

A Horn-style argument map.

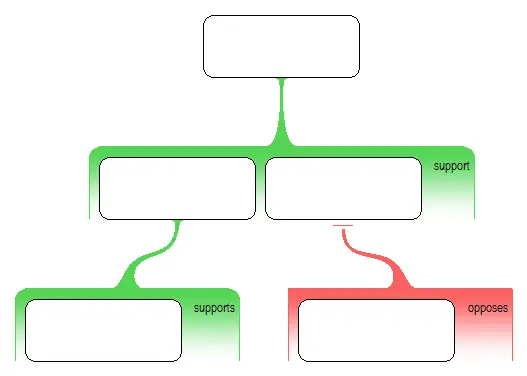

The most recent development has been the development of quality software tools dedicated to producing argument maps, such as Rationale.

Rationale -style map.

As you can see from these examples, there are many different kinds of argument mapping. What they have in common is the graphical display of evidential relationships - that is, how some things are evidence for or against others.

Argument mapping is a form of intelligence enhancement or augmentation. Using graphical techniques, it extends the power of the brain to process complex reasoning by allowing the brain to apply more of its resources.

More information on argument mapping

Follow these links for more general information about argument mapping. Note that you don't need to read these in order to do this tutorial.

- 'Argument Map' in Wikipedia

- The Homepage of Robert Horn

- Rationale, the leading software for argument mapping

Why Map Arguments?

There are many reasons to learn argument mapping, and to engage in argument mapping:

- Mastering the art of argument mapping will help build your general reasoning and critical thinking skills. Extensive studies suggest that instruction based on argument mapping is far more effective than traditional techniques for improving critical thinking.

- Argument mapping will help you produce clear, strong, well-organised arguments of your own. Suppose for example you have to write a "defend your opinion"-type essay. If you map out the relevant reasoning, you will become much more clear as to what it is, what you might need to add, strengths and weaknesses, and so forth.

- Argument maps will help you communicate your reasoning to other people (at least, to other people who are familiar with argument mapping). Ordinarily we present reasoning in prose, whether written (e.g., an essay) or spoken (e.g., a verbal debate). However prose is very unreliable for this job. Very often, the reader or hearer ends up forming quite a different interpretation of the reasoning than the one you intended. Argument maps are far more successful, because they present reasoning in a completely clear and unambiguous form.

- Argument mapping helps in the evaluation of reasoning, that is, deciding whether it is good or bad. Evaluation is crucial to critical thinking, since you should only accept things when they are backed up by solid reasoning. Argument mapping makes the structure of reasoning completely explicit, and so it helps you see strengths and weaknesses that would otherwise be obscured or hidden.

- Argument mapping helps people resolve disagreements rationally. Often in debates or arguments, everyone has a different "take" on what the arguments actually are. Using argument mapping, people can share a common conception of the structure of the reasoning, and so disagree about the substance of the issues rather than being sidetracked by misunderstandings.

- Similarly, argument mapping can help you make better decisions. Anytime you need to make a decision on an issue on which there is a complex tangle of arguments, you will be better off if you map out the arguments to gain clarity and perspective.

- Finally, argument mapping can be interesting and fun! Of course this is a matter of personal taste, but as a general rule, the better you are at something, the more interesting and enjoyable you find it. We all engage in reasoning and argument every day, but most people do it quite badly. Somebody who has mastered argument mapping is like an expert skier rather than a novice. For the expert, skiing is a far more challenging and satisfying activity.

About this Tutorial

What it covers

This tutorial cover the basics of argument mapping. More precisely, it covers two related topics:

- The basic structure of reasoning and argument in ordinary language. This is the fundamental stuff everyone should know about how arguments are constructed.

- How to produce diagrams (maps) of that structure. Argument mapping is a helpful technique for understanding the structure.

These two topics are heavily interdependent. It is very difficult to get clear about the structure - either the general principles, or the detailed structure in particular cases - without an effective technique such as argument mapping. Conversely, you can't produce good argument maps unless you have a good grip on the fundamentals of the structure.

There are two large topics which are not treated in this tutorial, even though they are very important:

- Evaluation. This tutorial says almost nothing about how to tell if reasoning is any good. It is concerned with structure, not quality. However clarity about structure is essential if you want to make sound judgments about quality.

- Identifying arguments. One of the hardest parts of argument mapping - indeed, one of the hardest of all intellectual tasks - is figuring out the reasoning buried in what somebody says or writes. A lot can be said on this topic; indeed, there could easily be another tutorial on that topic alone. In this tutorial, many of the examples and exercises involve reasoning as presented in written prose. However the focus is always on the essentials of argument structure, rather than the myriad issues involved in interpreting the prose. Very often, the prose has been modified so as to make interpretation easier.

Each set has two main parts:

- Theory, covering key principles and concepts

- Exercises, including a quiz.

Argument mapping is a complex skill, and this tutorial is designed to help you become proficient in that skill. Thus, the exercises are crucial. Don't make the mistake of reading the theory, and then just skimming over the exercises assuming that you've already got the idea. Do the exercises properly, and be sure to make your best attempt on each exercise before looking at the model answers. When doing the exercises, feel free to refer back to the theory pages whenever you feel like it.

In the theory part, central principles are wherever possiblepresented using a diagram, with a minimum of accompanying text. The basic idea is that you should be able to look at the diagram at the top part of each theory page and get the essential idea. Further down the page you will find some discussion which may help you understand the principle better.

The tutorial is progressive. That is, each set builds on the previous one. You should try to master the material in one set before moving on to the next one.

Contact...

Please contact us if you have suggestions, requests or queries.

Reading - Apollo Moon Landings

In this tutorial, almost all the examples and exercises are based on arguments over whether Apollo astronauts really did land on the Moon. In particular, they are drawn from an article Apollo Moon Landings, by Kevin Yates, who works at the National Space Centre in the UK.

You should download this article, print it out and read it carefully. The examples and exercises will make much more sense in the context of the whole article.

- Download Apollo Moon Landings.

- Numbers next to an example in the sets indicate the corresponding location in the text, e.g., (6.1) refers to page 6, paragraph 1.

Did the astronauts land on the Moon??

In our opinion, Apollo astronauts really did land on the Moon; the arguments by the "Moon landing hoax believers" are interesting but ultimately not persuasive. They are useful precisely because they are superficially plausible but turn out to be weak. Thus they illustrate the importance of careful analysis and evaluation, a process supported by argument mapping.

Producing Argument Maps

The exercises in this tutorial ask you to produce argument maps. Also, you might want to produce argument maps of your own, for study, work or just out of interest. So how do you go about actually creating an argument map?

There are basically three approaches:

By hand. You can always take out pencil and paper, ruler etc. and produce maps by hand. This is easier if you have one of those clear plastic templates which give you squares, rectangles, straight lines, arrows etc.. Producing maps by hand is easy and convenient for simple maps. However for more complicated maps it soon becomes impractical - especially when you need to make changes. (You always need to make changes!)

Generic software. You can use generic software with drawing or diagramming features; examples include Powerpoint, Visio, Inspiration and ConceptDraw. However this is a bit of a trap, compared with the other two methods. First, unless you use a very sophisticated package such as Visio, there are certain kinds of structures in argument mapping which it will be difficult if not impossible for you to create. Second, generic packages require that you have a high level of understanding of what you are trying to achieve, and even then producing even moderately complex maps is a very time-consuming business.

Argument Mapping Software. In general, the best approach is to use software built specifically for argument mapping. Currently available packages include Athena, Araucaria, and Rationale. Using specialised argument mapping software will help you construct and modify professional-looking maps quickly and easily. An added advantage of using such software is that it provides strong "scaffolding." That is, the only structures you can build are argument maps. If you use generic software, you have more flexibility, but this increases the chance of mistakes. As with most tasks, the right tools help you get the job done faster and at a higher standard.

Rationale

Almost all the diagrams in this tutorial were all created using Rationale (though many were edited further using a graphics program). Rationale is a general purpose argument mapping package. Rationale can be obtained from www.rationaleonline.com.

Printing Argument Maps

Arguments can get complicated, and a map of a complex argument can be very large. Simple maps can be printed on normal A4 or US Letter paper; you might find it helps to print in landscape mode.

As maps get more complicated, printouts need to be larger. An A3-size printer, if you can get access to one, is very useful. For maps that are larger still, you can either print on multiple pages, then stick them together by hand; or send your map to a specialist printing outfit.