Set 1: Simple Arguments

Set 1 is concerned with simple arguments - what they are, and how to map them. It covers:

- What simple arguments are.

- The two main kinds.

- How to map them.

- Some rules for producing proper maps.

Simple arguments are the most elementary units of reasoning. A proper understanding of how they work is essential for mastery of reasoning and argument more generally.

If you find this first set quite easy, just move through it quickly. Don't skip over it, however, since clarity on the fundamentals is crucial for later sets.

The examples used in Set 1 are all drawn from the article Apollo Moon Landings (pdf file). If you haven't done so already, you really should download this article and read it thoroughly. It would help a lot to have a printed copy with you. Numbers next to an example indicate the corresponding location in the text, e.g., (6.1) refers to page 6, paragraph 1.

1.1 Reasons

- A reason is a piece of evidence in support of some claim.

- A claim is an idea which somebody says is true.

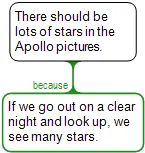

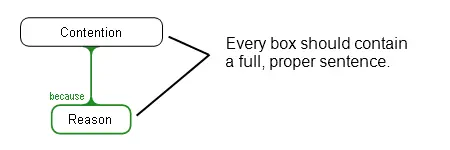

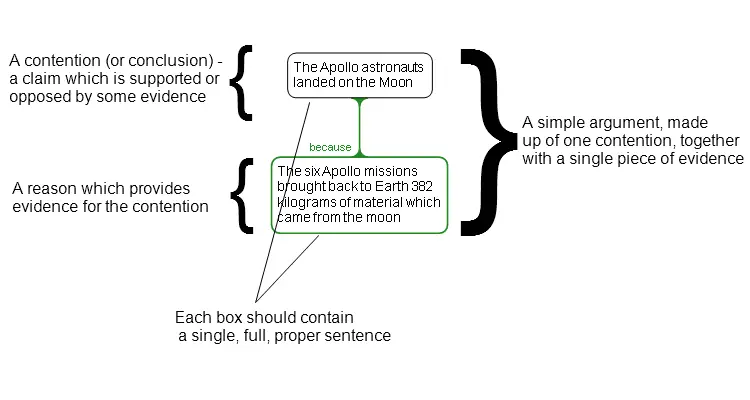

- To map a reason, put the reason and the claim in boxes, and link them together. Here is one way to do it:

Examples

Consider this piece of reasoning from Apollo Moon Landings:

There should be lots of stars in the Apollo pictures, because if we go out on a clear night and look up, we see many stars. (3.1)

Here, the claim being supported is There should be lots of stars in the Apollo pictures. The evidence is that when we go out on a clear night and look up, we see many stars. Here is how to map this reasoning:

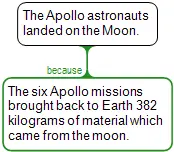

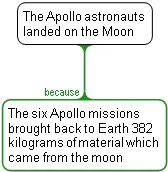

Here is another example:

The 382 kilograms of lunar material brought back to Earth by the six Apollo missions did come from the Moon. Therefore, Apollo astronauts must have landed on the Moon. (9.1-2)

Claim: The Apollo astronauts landed on the Moon.

Evidence: The six Apollo missions brought back to Earth 382 kilograms of material which came from the Moon.

Discussion

People use the word "reason" in many different ways. You'll see this if you look it up in the dictionary. In this tutorial, we are using the word in one specific way: to refer to a piece of evidence for a claim.

Technically, a piece of evidence (and hence a reason) consists of a set of claims presenting evidence that another claim is true. Don't worry if that doesn't make much sense right now; it will become more clear in Set 2.

There are lots of superficially different ways to map a reason. The key thing is to visually distinguish the reason and the supported claim, and to show the link between them. The mapping approach we adopt here is the one used in the Rationale™ software. Using this approach show that something is a reason by the use of (a) the colour green, for reason; and (b) the word "because" just above the reason.

Some reasons are good (strong, powerful, valid). That is, they provide strong evidence for the claim. Some reasons are terrible. This tutorial is concerned with the structure of reasoning, not its quality.

New Concepts

- A claim is a proposition put forward by somebody as true. A proposition is an idea which is either true or false.

- A reason is a piece of evidence in support of some claim. Technically, a reason is a set of claims working together to provide evidence that another claim is true. This will become more clear in Set 2.

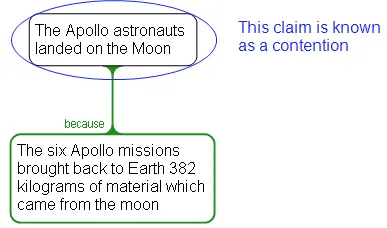

1.2 Contentions

A claim supported by a reason is called a "contention".

Discussion

The word "contention" is technical vocabulary. It is the special word we use for a claim for which some evidence has been provided.

Note that very often, logicians use the word "conclusion" where we are using "contention". Unfortunately "conclusion" is rather misleading in a number of ways.

New Concepts

- A contention is a claim for which some evidence is presented, whether for or against. Logicians often use the word "conclusion" to refer to a contention.

1.3 Objections

An objection is like a reason, but is evidence against a contention.

Examples

Consider the following passage from Apollo Moon Landings:

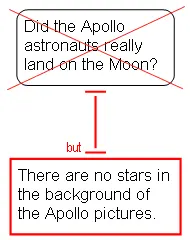

There are no stars in the background of the Apollo pictures. Therefore, Apollo astronauts did not land on the Moon. (3.0-1)

Here, we are given evidence against the idea that Apollo astronauts landed on the Moon. The contention is that Apollo astronauts landed on the Moon; the evidence (which goes against it) is that there are no stars in the background of the Apollo pictures.

Here is a map of the reasoning, showing the objection in red:

Here is another example:

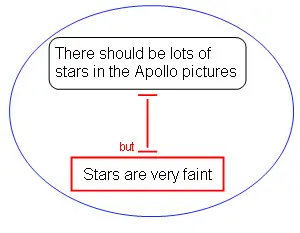

It is not true that there should be lots of stars in the Apollo pictures, because stars can be very faint.

The contention (the thing being objected to) is that there should be lots of stars in the Apollo pictures; the evidence is that stars can be very faint.

Discussion

Objections and reasons are very similar; it is just that while reasons present evidence supporting the contention, objections present evidence against it. Roughly, an objection "says why the contention wouldn't be true."

You may have noticed that a reason can be transformed into an objection, and vice versa, if you reverse the contention.

In the mapping approach used here, we show that something is an objection by the use of (a) the colour red, for objection; and (b) the word "but" just above the objection.

Technically, an objection is, like a reason, really a set of claims. This will become more clear in Set 2.

New Concepts

- An objection is a piece of evidence against some claim. Technically, an objection is set of claims working together to provide evidence that another claim is false.

1.4 Simple Arguments

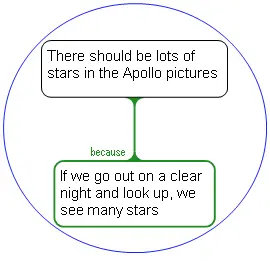

A simple argument is just a contention with a single reason for it, OR a contention with a single objection to it.

Here are two simple arguments:

Examples

The simple argument is the whole structure (reason AND contention).

This is another simple argument, made up of an objection to a contention. Notice that the contention happens to be the same as in the first example; for more on this see Set 3.

Discussion

Note that all you need for a simple argument is a single piece of evidence bearing upon a single contention. You don't need both a reason and an objection. In other words, a simple argument is not a debate; it is just an elementary piece of reasoning.

"Simple" doesn't mean small, short or obvious. A simple argument might be quite technical or hard to understand. What makes an argument simple is that it has just one contention and one piece of evidence.

This is important because the simple argument is the basic unit of all reasoning. All arguments, no matter how complex, are made up of simple arguments hooked up together. This will become more clear in Set 3 and 4.

New Concepts

- A simple argument is just a contention with a single piece of reason for it, or a contention with a single objection to it.

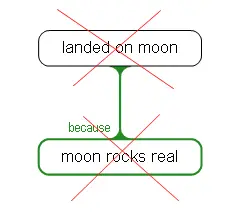

1.5 Use Sentences

When argument mapping, boxes should contain full, grammatical, declarative sentences.

Examples

Use complete sentences, not words or phrases:

|  Correct |

Use declarative sentences, not other kinds of sentences such as questions:

| Correct |

Discussion

It is very tempting to just use a word or simple phrase instead of a full grammatical sentence. This saves effort and space, and you feel as if you have the complete claim in your mind; all you need is a few words to indicate what claim belongs in that place.

However this is wrong. Reasoning is made up of claims, and you can't properly express a claim in anything less than a full grammatical sentence. Using a word or phrase creates a number of problems:

- You might never properly articulate the claim in your own mind.

- Somebody else reading the argument map has to try to guess what claim you had in mind, and often will guess incorrectly.

- As we will see later, without full sentences, you will not be able to apply some important principles of argument mapping.

Generally, using words or phrases rather than full sentences is sloppy thinking.

A declarative sentence is one which states a proposition which can be true or false. Some kinds of sentences are not declarative; for example, questions don't state propositions. Reasoning is a matter of the logical or evidential relationships among propositions, so you should always be using declarative sentences to express reasoning.

New Concepts

- A declarative sentence is one which states an idea which can be true or false.

1.6 No Reasoning in Boxes

You should avoid putting reasoning in boxes. In an argument map, boxes contain claims, not whole arguments.

The Apollo astronauts could not have survived the journey through the Van Allen Belt, so they cannot have been to the Moon. (6.4)

This box contains a simple piece of reasoning. | The correct way to map the argument is to display the reasoning. |

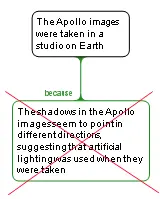

The shadows in the Apollo images seem to point in different directions, suggesting that artificial lighting was used when they were taken. Therefore they were taken in a studio on Earth. [Based on 5.1]

| ||

The reason here contains a simple argument. This means that there are two separate arguments being made. | Map each argument separately. |

Discussion

The whole point of argument mapping is to make the structure of reasoning completely explicit using graphical techniques such as boxes and arrows. If reasoning is inside a box, it is to some extent hidden away.

This is not just being pedantic. In following sets you'll see that many critical argument mapping techniques cannot be used unless and until we have fully revealed the structure of the reasoning.

1.7 Summary

Key Points

Note: don't put reasoning inside a box. Argument maps display the structure of reasoning; don't hide that structure inside a box.

New Concepts

- A claim is a proposition put forward by somebody as true. A proposition is an idea which is either true or false.

- A reason is a piece of evidence in support of some claim. Technically, a reason is a set of claims working together to provide evidence that another claim is true.

- A declarative sentence is one which states an idea which can be true or false.

- A conclusion is a claim for which some evidence is presented, whether for or against. See also contention.

- An objection is a piece of evidence against some claim. Technically, an objection is set of claims working together to provide evidence that another claim is false.

- A simple argument is just a contention with a single piece of reason for it, or a contention with a single objection to it.

Quizzes

The quiz is designed to help you learn the material. In all cases, you should choose the best answer. In many questions, there are answers which are partially correct, but are not the best response.

Quiz scoring is based on the number of answers you select, not simply on the number you get correct first time. You can get partial credit for selecting the correct answer with subsequent guesses.

Go to Set 1 Quiz #1

Go to Set 1 Quiz #2

Exercise 1.1

Task

Create an argument map of this simple argument:

Reason: The shadows in the Apollo pictures seem to point in different directions.

Contention: Artificial lighting was used when taking the pictures.

Note: for more information about creating argument maps, see the page Producing Argument Maps.

Click on the image to open it in the editor. Note: editor will open in a new window.

Exercise 1.2

Task

Create an argument map of this simple argument:

Contention: The Apollo astronauts landed on the Moon.

Objection: The Apollo pictures were taken in a studio on Earth.

Click on the image to open it in the editor. Note: editor will open in a new window.

Exercise 1.3

Task

Consider this passage from Apollo Moon Landings:

There are two main points those who promote the hoax claims raise about the shadows in the Apollo images. Firstly, the shadows seem to point in different directions. Secondly, the astronauts seem well lit at times when they should be in shadow. Both these arguments suggest that artificial lighting was used and therefore the pictures were taken in a studio on Earth. (5.1)

The passage contains three simple arguments. One of them was Exercise 1.1. Identify another different simple argument, and create an argument map of it.

Click on the image to open it in the editor. Note: editor will open in a new window.

Exercise 1.4

Task

The following passage (based on 5.0-1) contains a simple argument based on an objection. Create an argument map of that simple argument.

The Apollo pictures were taken in a studio on Earth. Therefore, it is not true that the Apollo astronauts landed on the moon.

Click on the image to open it in the editor. Note: editor will open in a new window.

Exercise 1.5

Task

Create an argument map of the simple argument contained in the following passage from Apollo Moon Landings. Note that you will need to:

- identify the key claims.

- determine whether the text is presenting a reason or an objection.

- enter the claims on an appropriate argument map.

The flag only actually moves when, or just after, the astronauts have touched it. This suggests that the movement is the result of vibrations travelling through the solid pole and disturbing the flag.

Click on the image to open it in the editor. Note: editor will open in a new window.

Exercise 1.6

Task

Create an argument map of the simple argument or arguments contained in the following passage from Apollo Moon Landings. Note that you will need to:

- identify the key claims.

- determine how many simple arguments the passage contains.

- produce an argument map of the simple argument(s).

The tyres of the Lunar Roving Vehicle have also been brought into question, as many think they would be likely to explode in the vacuum of space. Again, a simple bit of homework reveals that the tyres were not of the traditional, inflated rubber kind. The purpose-built LRV tyres were actually made from a mesh of zinc-coated piano wire, to which titanium treads were riveted in a chevron pattern. [8.5]

Note: you'll probably find that it helps you to read the passage in the context of the surrounding paragraphs in Apollo Moon Landings (p.8).

Click on the image to open it in the editor. Note: editor will open in a new window.