Advanced Reasoning

Advanced Reasoning Argument Maps

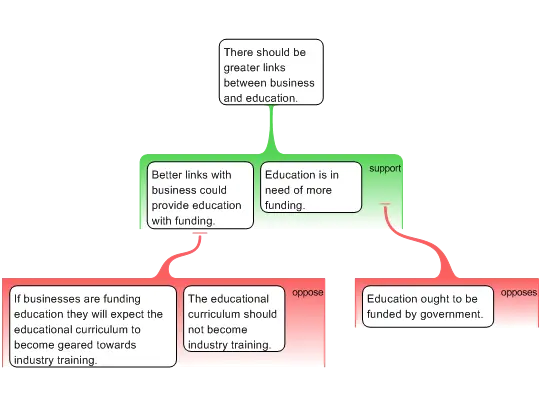

Advanced reasoning argument maps are the most powerful means for developing advanced critical thinking skills.

They are very similar to Reasoning maps, but they are much more precise and detailed in four ways:

- They require more precision in the way the claims are expressed.

- They break down each reason and objection into the multiple claims (premises) that make it up, prompting the user to articulate the co-premises in an argument.

- They distinguish between support or opposition to claims and support or opposition to inferences.

- In evaluation they distinguish between the truth or acceptability of a claim on one hand and, on the other hand, the strength or validity of the inference from a set of claims (a reason or objection) to another claim.

See also...

What is Advanced Reasoning?

Advanced Reasoning FAQ

Introduction

Advanced reasoning is another form of argument mapping that provides co-premise structures and additional evaluation options.

You can start a map in reasoning mode and switch to advanced reasoning, for instance if you want to show a co-premise that may be an assumption. You may also prefer the look of advanced maps and use them without co-premises.

Evaluating advanced reasoning maps provides the option to evaluate the premises and evaluate the strength of the reason as a whole.

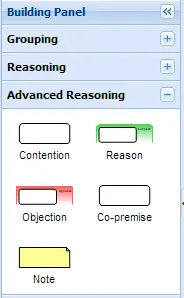

Advanced Reasoning Panel

The advanced reasoning panel on the left side of the workspace contains all you need to build advanced argument maps. You can drag and drop reasoning boxes including co-premises, templates, a quick start template, an example and a legend.

What is Advanced Reasoning?

The most advanced form of argument mapping in Rationale is supported by the advanced reasoning map format. Practicing this advanced, or analytic argument mapping is the most powerful means for developing advanced critical thinking skills.

This is a quick introduction to the principles of advanced reasoning. We strongly recommend that you familiarize yourself with reasoning maps prior to the advanced format.

Basic building principles

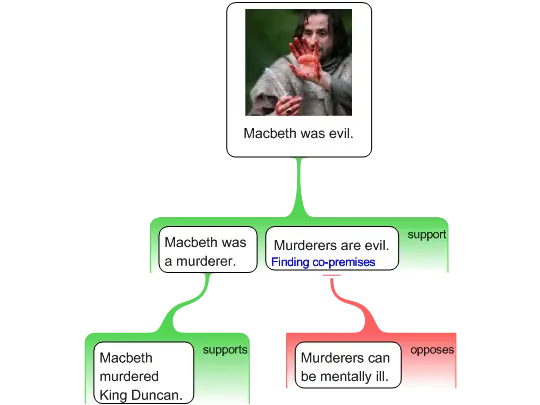

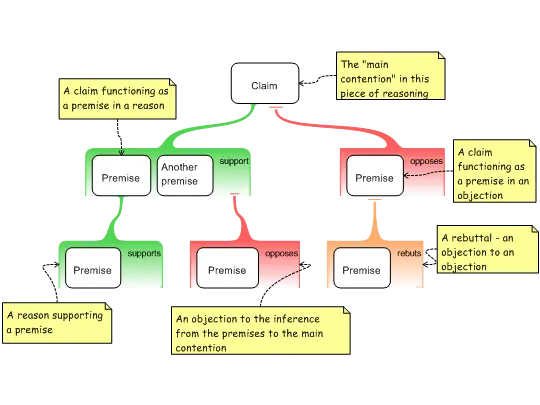

Advanced reasoning argument maps are made up of four box types:

- Contention; the statement being asserted or considered.

- Reasons; a claim that states why one should accept or reject another claim. In advanced maps, the reason can contain multiple claims or premises.

- Objections; a claim that states why one should reject another claim. which are reasons to reject whatever's above them. Objections to objections are called rebuttals and are represented orange in Rationale. Objections and rebuttals can have multiple premises.

- Premises; These are distinct claims which form one reason. There is a main premise and co-premises.

Study the map schema below to understand the basic building principles:

Premises

In Advanced Reasoning we can distinguish between premises belonging to the same reason (linked) and premises belonging to distinct reasons (convergent). Roughly:

- Two (or more) premises belong to the same reason if they must both/all be true in order for the reason to be relevant to the claim above it, i.e. if one cannot support the claim above it without the other

- Premises belong to separate reasons if they are unrelated - if they can support the claim above independently of one another. These principles also apply to objections.

When do premises belong to the same reason or objection?

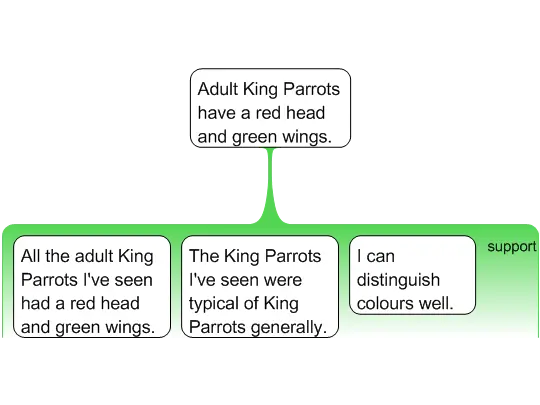

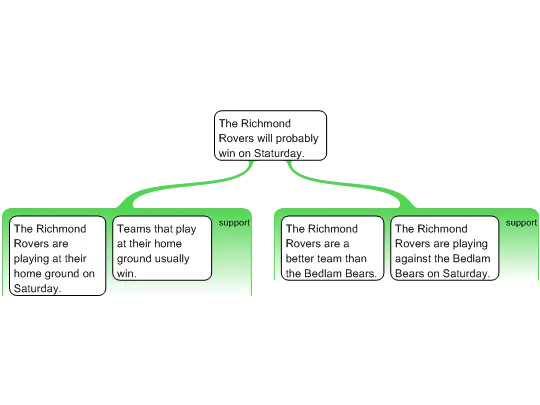

Here are some examples of linked premises. In each case, if you suppose one of the premises to be untrue then you'll see that the reason can't support the claim above it - it will be irrelevant.

If the Rovers are not playing on their home ground on Saturday, the fact that teams that play at their home ground usually win becomes irrelevant to whether or not the Rovers will win on Saturday.

Similarly, if it's not true that teams that play at their home ground usually win, the fact that the Rovers are playing at home on Saturday becomes irrelevant to whether or not they are likely to win.

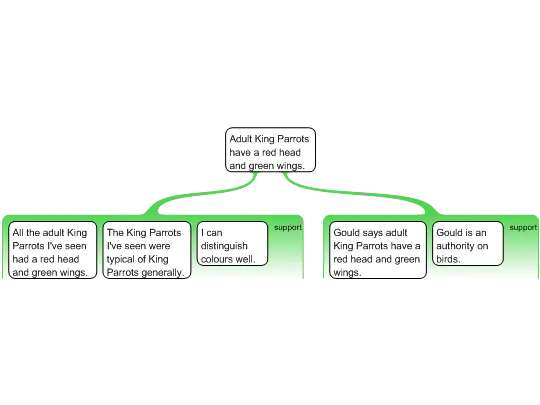

If I've seen another colour adult King Parrot, or if the King Parrots I've seen weren't typical, or if I'm bad at distinguishing colors - if any of those things were the case - then this reason can't support the claim above it.

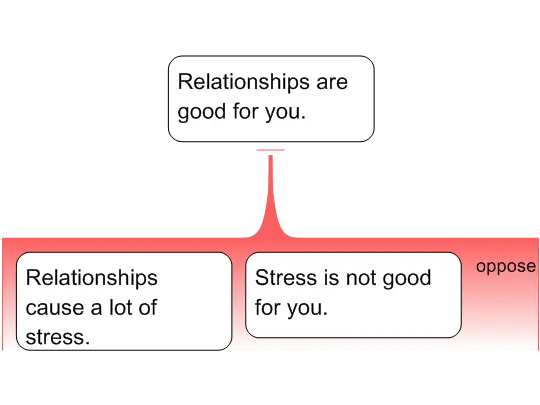

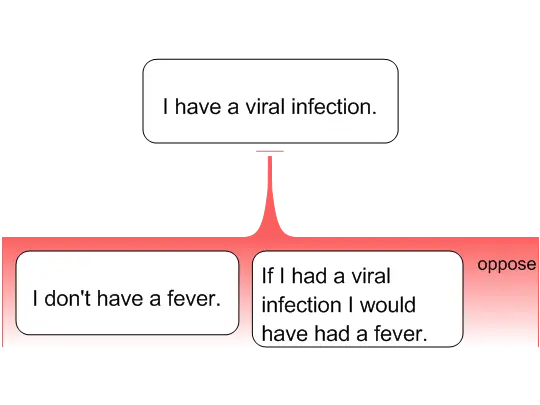

Similarly, if a premise in an objection is not true then the objection does not oppose the claim above it.

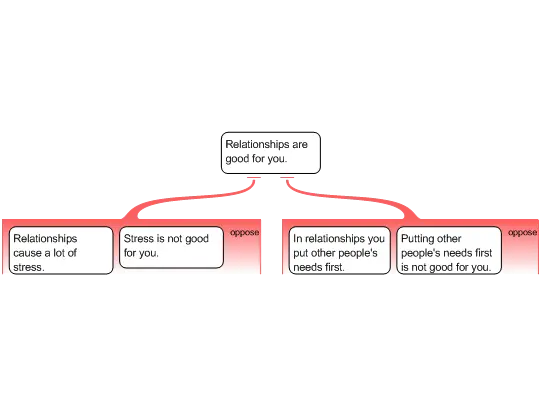

If relationships don't cause a lot of stress, then the fact that stress isn't good for you becomes irrelevant for opposing that relationships are good for you.

Similarly, if it's not true that stress is not good for you, the fact that relationships cause a lot of stress isn't relevant to opposing the claim that relationships are good for you.

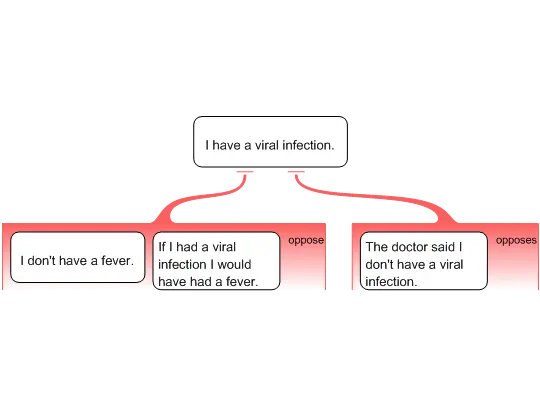

If I do have a fever, or if it is not the case that viral infections and fevers go together, then this objection doesn't undermine the claim above it.

Please note that these are simply examples: we are not necessarily saying that they are good arguments, or that the claims are true!

When do premises belong to separate reasons?

Here is an example where the premises within each reason are linked, but there are separate and unrelated reasons (or objections) bearing on the contention:

The home ground advantage is one reason for thinking the Rovers will win; the fact that the Rovers are a better team is a separate, distinct, additional reason for thinking that they will win.

Here are two separate considerations bearing on the contention: one is my personal experience, the other is information provided by an expert.

Stress and putting one's own needs first are two different issues, but they both independently bear on the contention.

If the doctor used a different test to tell whether I have a viral infection - a test other than whether or not I have a fever - then the doctor's opinion is a separate objection to the contention. If I sought yet another doctor's opinion, then that opinion would be a third consideration bearing on the contention.

Assumptions and inference objections

We don't usually state all the premises in an argument - we leave them as unstated assumptions. Unstated assumptions may well be true and are often trivial; but sometimes they are false or deeply problematic, so it's worth bringing them out in an argument map so you can support or oppose them like any other claim. In fact, false hidden premises are the most common problem with bad arguments.

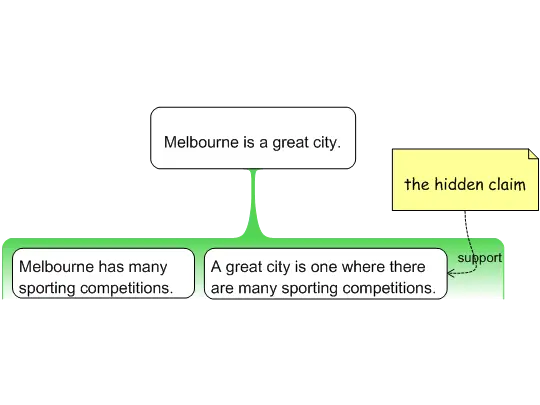

The easiest way to see the usefulness of spelling out hidden premises is in inference objections.

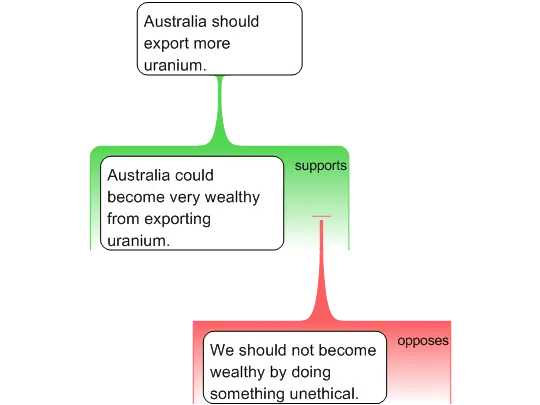

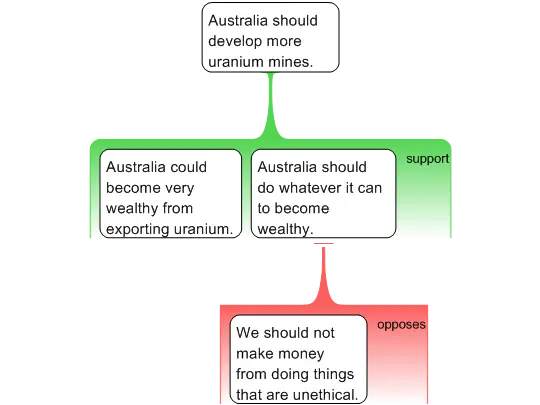

The claim 'We should not become wealthy by doing something unethical' is not an argument against the claim that Australia could become very wealthy from exporting uranium. The objection is not denying that Australia could become wealthy this way.

Instead, it's an objection to the inference from Australia's prospective wealth to the contention that it should therefore export more uranium.

One way to think of an inference objection like this is as an objection to a hidden premise or assumption. We've made this explicit here.

Rebuttals can also be inference objections.

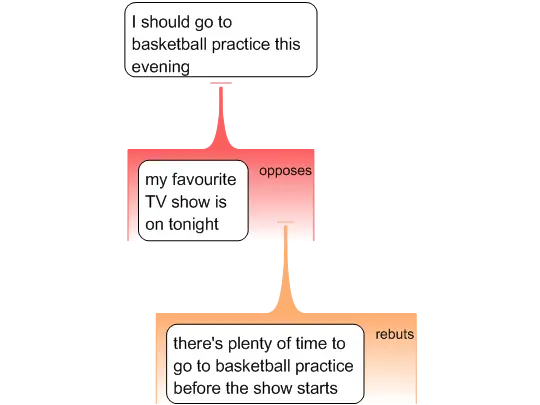

The claim 'There's plenty of time to go to basketball practice before the show starts' does not oppose the claim that my favorite TV show is on tonight.

Instead, the rebuttal shows that the fact that my favorite TV show is on tonight is not a good excuse for getting out of basketball practice!

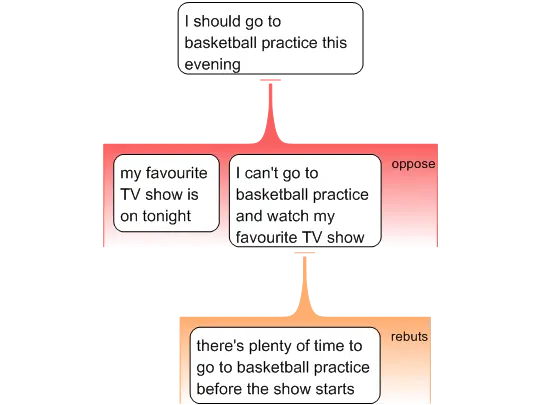

Here's the rebuttal mapped as an objection to the inference.

This is one way of treating it as an objection to a hidden premise (assumption).

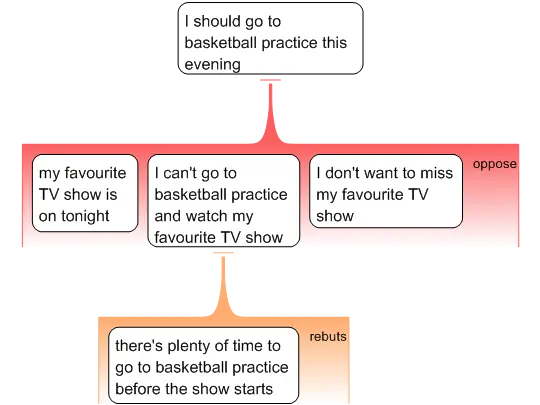

Here's another way of treating it as an objection to a hidden premise (assumption).

Click here for more on inference objections

Inference objections

An inference objection is an objection that arises from a premise that is inferred but not stated. In Rationale's advanced reasoning maps you can show an inference objection by placing the objection to the right of the stated premise.

For example;

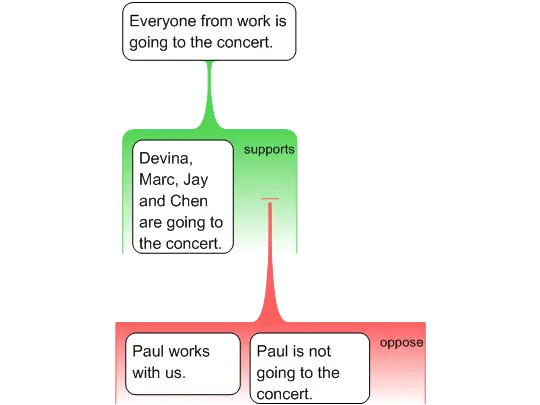

Although it may be true that Devina, Marc, Jay and Chen are going to the concert, this is not enough to establish that everyone from work is going to the concert, because Devina, Marc, Jay and Chen are not the only people at work. The objection does not object to the main premise but to the inference that arises from it, i.e. that the stated people are in fact everyone from work.

To be more precise, a co-premise should be included to state "Devina, Marc, Jay and Chen are everyone from work."

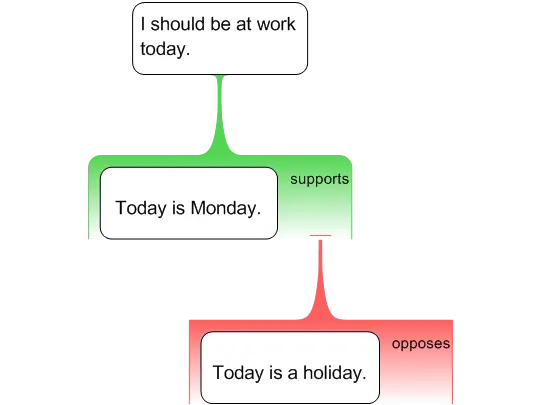

In this example, I may accept as true that today is Monday but there is an important inference or assumption being made - that I should be at work on this Monday. The inference objection that could be raised is that today is a holiday or perhaps that I am sick. So where the claim is not articulated, I add an objection to the right of the stated claim which indicates that I am objecting to an unstated but implicit claim.

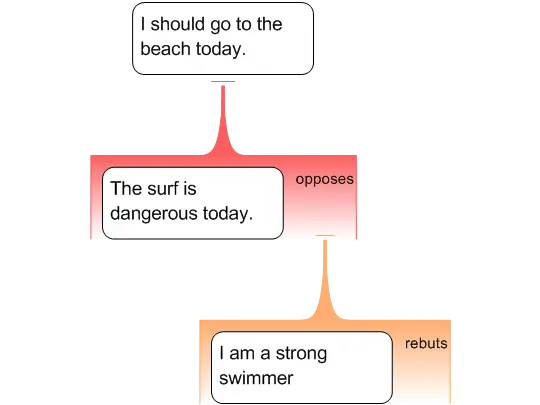

This is a little trickier because it is a rebuttal to an objection, but the principle is the same.

I accept that the surf is dangerous, but I think the fact that I am a strong swimmer counteracts it, so that the dangerous surf should not deter me from going to the beach.

Back to What is Advanced Reasoning?

Advanced Reasoning FAQ

Advanced Reasoning Maps

Why do these maps look different from reasoning maps?

The difference in the look is due to the inclusion of two main features. Firstly, advanced reasoning maps include the ability to add extra claims to reason or objection boxes. This is so you can "unpack" a reason and locate its co-premises. The second reason is the evaluation feature. In reasoning maps you decided if reasons and objections were strong, weak or had no impact upon the claim above, whereas in the analysis mode you have a twofold evaluation process. First you determine the truth of a claim and second, the strength or validity of the inference from a set of claims to another claim.

Why are there more than one claim box inside a reason or an objection box?

There can be one or more claims inside a reason box to ensure that the reason is fully articulated. This means that all hidden premises or assumptions are disclosed.

What's the difference between a claim and a reason?

A claim is a sentence that someone puts forward as true. A claim can be the contention, a reason, an objection or a rebuttal. A reason is a claim, or a series of claims that provides support or evidence for another claim. Reasons can comprise more than one claim.

How many white boxes go inside a green box?

You can place as many claim (white) boxes as are required inside the reason box. Nonetheless, if you use more than a few, you may be introducing a different reason, rather than breaking one reason into its separate claims.

Why is there more than one claim box in some reason boxes but not in others?

You use additional claim boxes as required. This means that you use more than one claim box when a reason needs more analysis or unpacking. For instance, if there is a hidden claim (also known as a hidden premise) then it needs to be illustrated (see example 1).

Example 1:

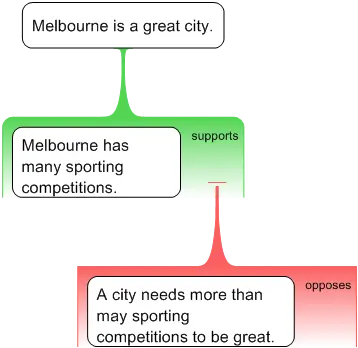

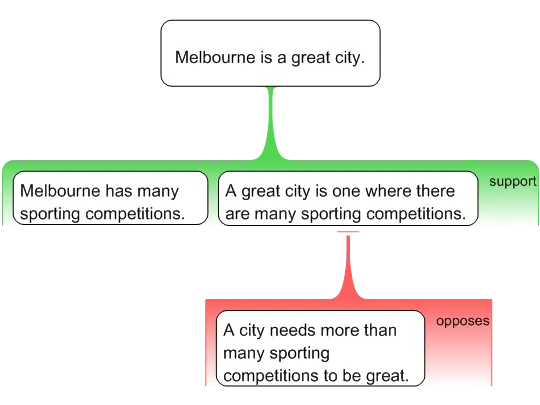

Sometimes, you may have an objection to the reason but it may not relate directly to one claim, rather it may object to the inference from the reason. In this case, the additional claim (hidden premise) needs to be added and the objection related to that additional claim (see example 2). (Also refer What is Advanced Reasoning? and Inference objections).

Example 2:

How come the arrows point to different areas in the reasons and objections?

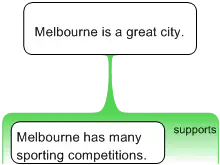

Lines signify the connection between claims. When you have a line joining one claim with another, this shows there is a direct relationship between them, for example, one is a claim in support of the other. Sometimes you may have a line connecting the reason (the green section of the box) but not a specific claim in that box. For instance, in the first map above, the objection does not oppose the claim that "Melbourne has many sporting competitions," however it does oppose the inference or assumption that arises from this reason. The line illustrates that it is opposing the reason but no specific claim in the reason. It is preferable to display all the claims in a reason, because this shows all the assumptions. Hence, in the second map, this claim is articulated "A great city is one where there are many sporting competitions." This is the claim that the objection directly relates to, hence the line reflects this relationship. (See inference objections).

If you want to do argument mapping do you only use analysis maps or do reasoning maps count?

Both reasoning and advanced reasoning maps are argument mapping formats. If you want to achieve a basic argument mapping form, then reasoning maps suffice. However, if you want to do a more thorough job, disclosing all claims and evaluating them more rigorously, then advanced reasoning maps is the option to choose.

Who do you recommend should use advanced reasoning maps?

Anyone who wants to disclose hidden claims and perform rigorous evaluation should use these maps. Having said that, advanced reasoning maps should generally be used after you have some understanding of argument mapping in the reasoning mode. They would generally be challenging for students learning about reasoning before the latter stages of secondary school.

I like the appearance of advanced reasoning maps better than that of reasoning maps. Can I use this, or do I have to have all those extra white boxes filled in?

Yes, you can use the advancedmaps without using all the features. Simply use one claim per reason.

The maps look like a series of roots. Is this deliberate?

Yes, we wanted an "organic" feel, just as ideas and reasons grow and emerge. Argument maps are also referred to as argument trees, so analysis maps fit this idea very well.

How do I evaluate an advanced reasoning map?

You can find help with this in the Evaluating.

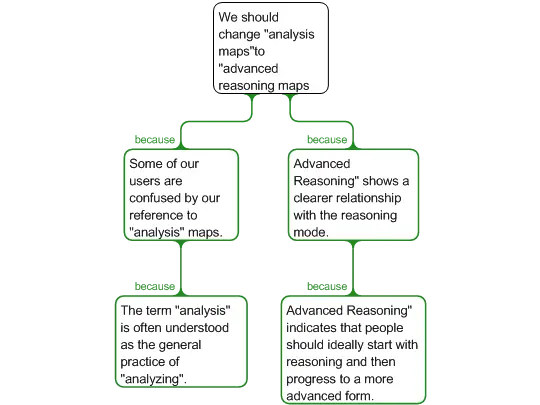

What's happened to the "analysis" maps?

These are them! Advanced Reasoning maps are indeed Rationale's pre Version 2 analysis maps. We have changed the name because...

Advanced Reasoning: Examples

Click on the image to open it in the Rationale Editor.

Quick Start:

Example:

Legend: