Reasoning

Reasoning maps

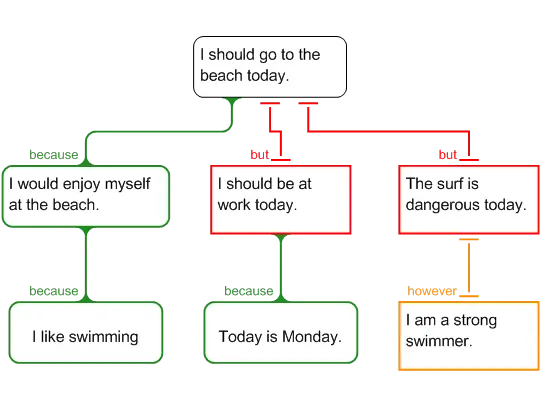

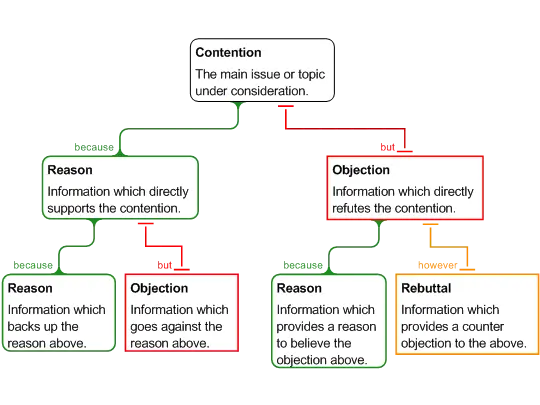

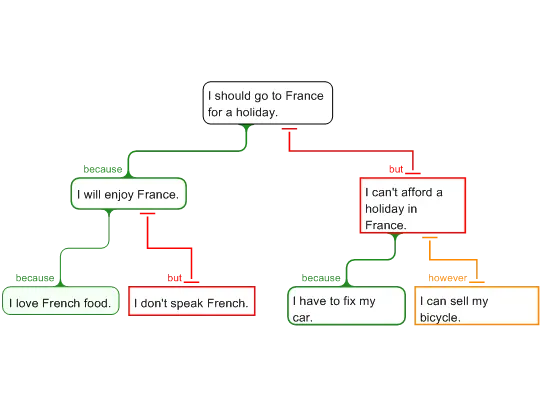

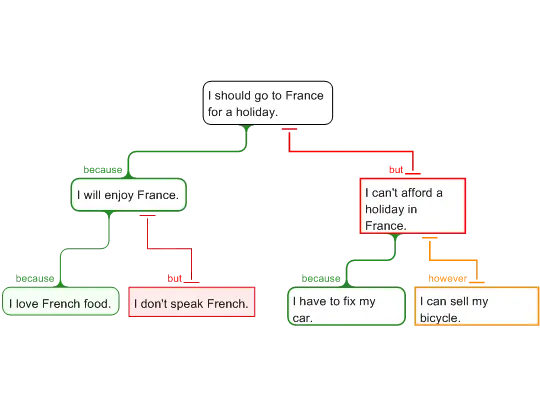

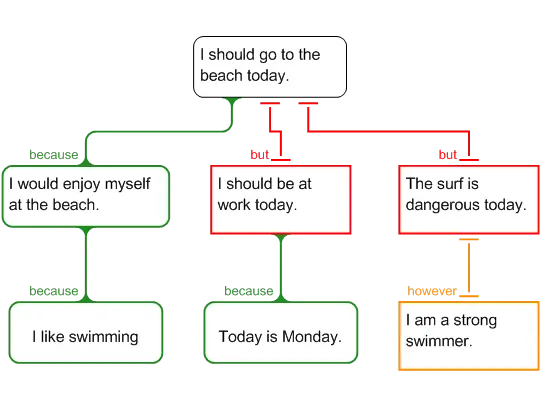

In a Reasoning map you identify a claim that expresses a contention on a subject, then give reasons for and against (objections to) that contention. The contention box is white and located at the top of the map. Reasons supporting the position are located underneath the contention and are colored green while objections are colored red to signify opposition to the contention. The boxes underneath the reasons and objections provide support or opposition to the reason or objection directly above them.

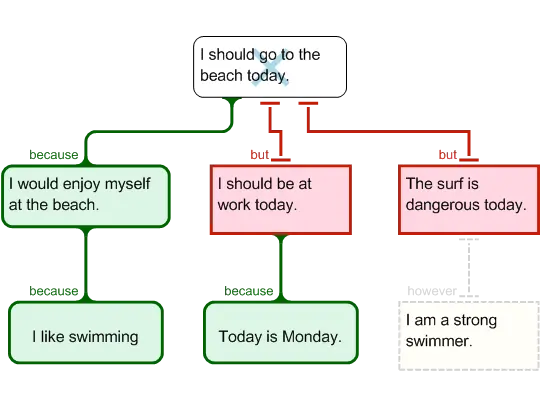

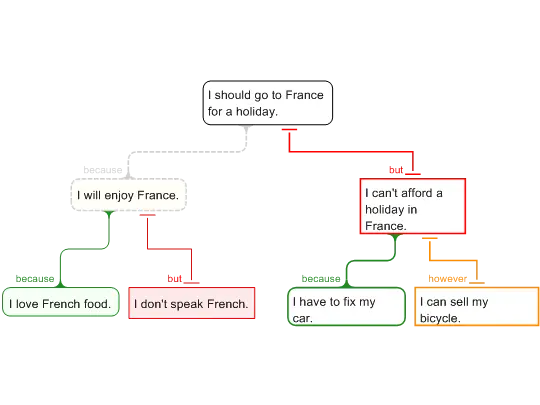

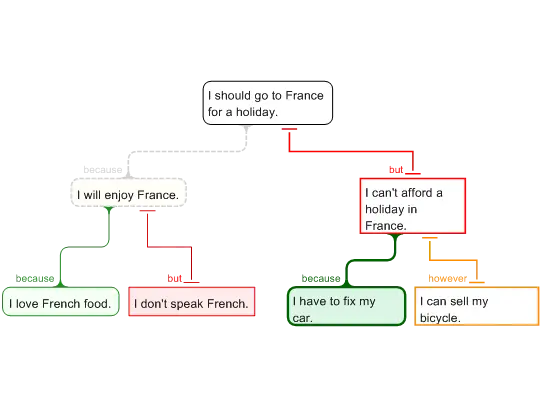

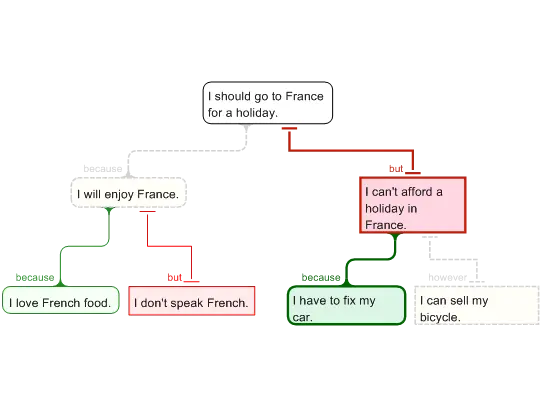

Rationale provides an evaluation feature which allows you to record your judgments on a map. Rationale represents your judgments by adding colour inside the boxes, changing the lines and (optionally) adding icons. These conventions show the strength of each reason and objection as well as your final assessment of the contention. Recording your judgments in this way takes a load off your memory and makes it easier to make a systematic, considered assessment.

See also...

What is reasoning?

Reasoning FAQ

Introduction

Reasoning or argument maps structure reasoning for any issue. They identify the claims and indicate their relationships to one another.

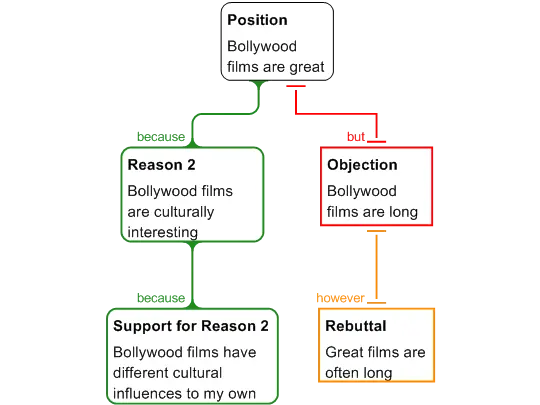

Reasoning maps lay out an argument so that everyone is clear what is going on! The white box is the contention, green boxes are reasons, red boxes are objections and orange boxes are rebuttals (these are created automatically when there is an objection to an objection).

You can map your reasoning, map other people's reasoning or use a map to keep track of everyone's ideas.

You can also add basis boxes to show the source of claims, evaluate the claims, add hyperlinks and images, drag in information from the web or your scratchpad and you can "upgrade" your reasoning map to an advanced reasoning map to identify assumptions.

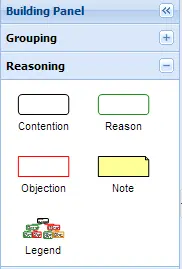

Reasoning Panel

The reasoning panel on the left side of the workspace contains all you need to build reasoning maps. You can drag and drop reasoning boxes, templates, a quick start template, an example and a legend.

What is Reasoning?

A Reasoning map in Rationale enables you to do basic argument mapping - a visual way to understand an argument. In a Reasoning map, you treat each reason and objection as a single sentence.

Basic mapping principles

Every Reasoning Map is made up of three kinds of things:

- Contention is a statement of the main point (proposition or position) being argued for or against . There can be only one Contention in a Reasoning map - at the 'top' of the map.

- Reasons are the claims for believing whatever's in the box above them (which could be the contention, another reason or an objection).

- Objections are claims which seek to refute another claim (which could be the contention, a reason or another objection). In the case of an objection to an objection, this is referred to as a rebuttal.

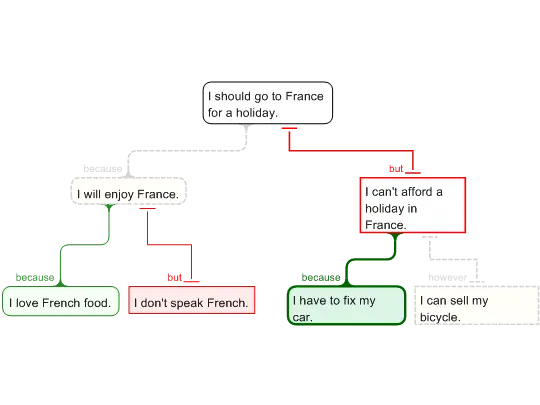

Study the map below to understand the basic building principles. The main thing to note is that green and red doesn't mean 'for' and 'against' the main point (contention), but 'for' and 'against' whatever is in the box immediately above them.

Reasoning Map Construction Process

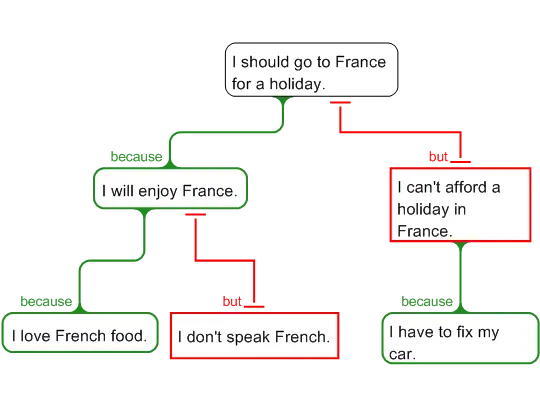

Suppose I'm wondering whether or not to go to France for a holiday and I want to map my reasoning to help me decide:

| I start with the central issue I'm considering, express it as a statement and put it in the contention box. At this stage it is just a statement or contention, it is not the conclusion until the argument has been laid out and evaluated. |

|---|

| My reason for thinking that I should go to France is that I think I'll enjoy France. I put my reason in a (green) reason box underneath the contention- and I've just mapped a basic argument! |

|---|

I can also form another argument by giving a reason against the contention I started with:

| A reason against going to France for a holiday is that I can't afford it! A reason against something is an objection to it - so I put it in an objection box (red) underneath the contention. |

|---|

That was two maps; but since they are for and against the same contention we can put them together on the same map:

I can add as many reasons and objections as I like; but let's keep it simple. I can support both my reason and my objection by giving reasons for them.

| Why do I think I'll enjoy France? Because I love French food. Why do I think that I can't afford a holiday in France? Because I have to fix my car. |

|---|

I can also question or challenge anything on my map by objecting to it.

What might be a reason to believe that I might not enjoy France? I don't speak French, for a start - which could be a little daunting! I add this as an objection under the thing I'm challenging.

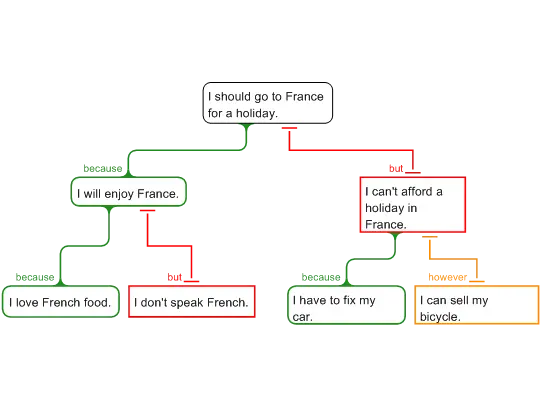

And I can rebut my original objection, i.e. give an objection to it. Is it true that I can't afford a holiday in France? Perhaps I could afford one, if I sold my bicycle... This is 'red on red' - an objection to an objection - which is called a rebuttal and is represented orange.

This is all you need to know to get mapping in Reasoning mode. You can build much more complex arguments by using these principles.

Here's the big secret: Have you noticed that there's a statement in each box? You can add red and green boxes to any box containing a statement, because you can give reasons for and against believing any statement on a Reasoning map. So you can make a truly complex argument by adding more reasons and objections bearing on the contention, then adding reasons or objections for the reasons and objections, then adding reasons and objections for each of those... and so on until you've reached a situation beyond which there's no point arguing (hopefully, because you've reached a situation where your argument rests on claims that are obviously true).

In some cases, it is important to show on your map the foundation on which each 'bottom' reason or objection rests, e.g. the source of the information. To do that, use a BASIS BOX from the Building Panel. Inside each basis box you can find an explanation of what it's used for - or you can make your own by using the blank one. For more information on basis boxes see the FAQ.

Once I've mapped all the reasoning I have a clear picture of all the considerations for and against the contention. But should I go to France or not? How does the map help me decide?

Basic evaluation principles

To make a decision about whether or not I should go to France I have to assess all the arguments for and against the contention and then judge whether to accept the contention (so I should go to France) or reject it (so I should not go to France). First, I must assess each consideration in turn.

Rationale uses colour coding to mark the strength of reasons and objections.

Let's start with my primary (top-level) reason, that I'll enjoy France. How well does that support the contention? In order to answer that question I have to consider the arguments I've given for and against it.

Is the fact that I love French food a good reason for thinking that I'll enjoy France? It's reasonable, but I can also get good French food in Melbourne and elsewhere in the world, and eating is only part of what I do on a holiday, so loving French food is not a very strong reason for thinking I'll enjoy France. I judge it as fairly weak. (Rationale colour codes it pale green and puts an optional single green dot next to it.)

What about the objection that I don't speak French? How much would that stop me enjoying France?

Well, I could go with a tour group, or buy myself a good phrase book, and count on finding French people who speak English. So it wouldn't completely wreck my experience; but it wouldn't be all that comfortable either, so I rate this as a weak objection. (Rationale colour codes it pale red and puts an optional single red square next to it.)

So given a weak reason to believe that I'll enjoy France, and a weak objection to it, what do I make of my reason?

I feel I can't really make up my mind. Perhaps I need to think about this a bit more, come up with some more considerations - reasons or objections. In any case, is enjoying France a good enough reason to think I should go there for a holiday? I might enjoy another place even more.

On the whole, I don't think this reason lends any support at all to the idea that I should go to France for a holiday. (Rationale represents this with a grey dotted line.)

Now let's look at the other primary line of argument, the objection that I can't afford a holiday in France. How strong is it? Again, I start by looking at the considerations bearing on it.

The fact that I have to fix my car is a strong reason to believe that I can't afford a holiday in France, since I know that fixing the car will be quite expensive and I'm not very rich! (Rationale represents a strong reason as dark green, with two optional green dots next to it.)

How strong is the objection that I can sell my bicycle? Will that help me afford a French holiday?

No way! My bicycle's worth next to nothing, while French holidays cost a lot. So this objection fails to rebut the original objection that I can't afford a holiday in France. (Rationale represents this useless consideration with a grey dotted line.)

So where does this leave my primary objection? I can immediately see that it's well supported. But how strong an objection to the contention is it? Actually, I think it's quite strong. If I can't afford it, I shouldn't go. (Rationale shows a strong objection as dark red with two optional red squares next to it.)

Now I can judge the contention and decide whether or not to book that holiday.

Looking at the primary considerations, I can see that there's a questionable reason that, as it stands, offers no support, and there's a strong objection. Given this reasoning, I should reject the contention. No French holiday for me this year! (Rationale represents my misfortune by placing a cross in the contention box.)

See also:

Reasoning FAQ

Reasoning FAQ

Reasoning Maps

Can one claim [a contention, reason or objection] have both a reason and an objection?

Yes, in fact this shows you have considered two perspectives - a reason to support and an object to refute another claim. If you were arguing for a contention, an objection would identify what someone else would contend, and this gives you the opportunity to think of a rebuttal. On the other hand, you may be creating a reasoning map to determine what to do or what to think - so working through all the objections and reasons is an important stage in ascertaining whether to accept or reject a contention.

What part of the argument should I start with - the top or the bottom?

Generally speaking, starting at the top is a good place because it focuses your attention on the contention or main point. Then you can consider the primary reasons and/or objections supporting or refuting this claim followed by supporting reasons and objections/rebuttals. What you will notice is that as you go down each level, the reasoning or evidence becomes more specific, while more general claims are on the top layers.

On the other hand, you may have many pieces of information or evidence from which you would like to draw a conclusion. In this case you may wish to group your evidence and formulate higher level claims as you progress.

Can I start with separate boxes and then link them?

Absolutely. Rationale gives you the freedom to work in the way that best suits your task and your style of working. It may suit your purpose to have your ideas or reasons and objections as separate boxes and then treat them like a jigsaw, working out how they all fit together. If you do this you may find that what you first thought were lower level reasons turn out to be rebuttals (objections to higher level objections).

When do you detach a reason from another reason?

You may realize that a reason is not actually supporting another reason but is in fact a separate reason bearing upon another claim. In this instance, you would detach the reason - either dragging it onto another box where it does relate or else onto the workspace, where you can "park it" to be later deleted or added to an argument as required.

How do I choose a rebuttal?

There is no rebuttal (orange) box as such that you drag and drop onto your workspace. Rather, you choose an objection and if it is a rebuttal (an objection to an objection) then Rationale will automatically recognize it as such and colour it accordingly.

Do all green boxes represent the affirmative side [supporting case] and red boxes the negative side [opposing case]?

Not necessarily! Usually someone who wants to support a contention will give reasons and supporting reasons but they will also provide rebuttals to the opposing side's argument. In this case, this rebuttal is orange because it is an objection to an objection. Similarly, someone who disagrees with a contention will provide objections, but they will also give reasons to support these objections, so again there is a mixture of red and green boxes.

Aren't reasons only given to support a contention? Why are there green boxes underneath the objection?

Reasons are given to provide support to a contention - but they are also used to support any other claim. So if I have an objection, then I will want to convince other people that it is a good one by giving them supporting reasons.

How do I evaluate a reasoning map?

You can find help with this in the Evaluation FAQ.

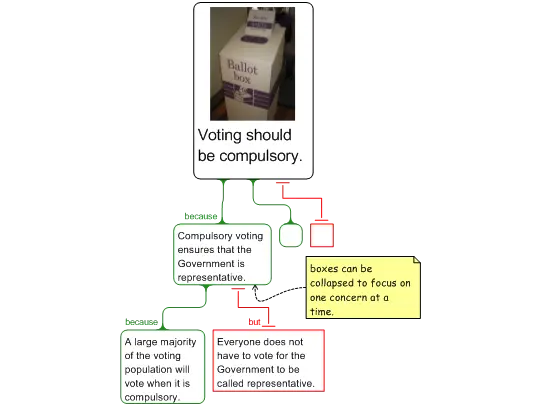

Reasoning: Examples

Click on the image to open it in the Rationale Editor.

Quick Start:

Example:

Legend: